How System Prompts Define Agent Behavior

This post was co-authored with Srihari Sriraman

Coding agents are fascinating to study. They help us build software in a new way, while themselves exemplifying a novel approach to architecting and implementing software. At their core is an AI model, but wrapped around it is a mix of code, tools, and prompts: the harness.

A critical part of this harness is the system prompt, the baseline instructions for the application. This context is present in every call to the model, no matter what skills, tools, or instructions are loaded. The system prompt is always present, defining a core set of behaviors, strategies, and tone.

Once you start analyzing agent design and behavior, a question emerges: how much does the system prompt actually determine an agent’s effectiveness? We take for granted that the model is the most important component of any agent, but how much can a system prompt contribute? Could a great system prompt paired with a mediocre model challenge a mediocre prompt paired with a frontier model?

To find out, we obtained and analyzed system prompts from six different coding agents. We clustered them semantically, comparing where their instructions diverged and where they converged. Then we swapped system prompts between agents and observed how behavior changed.

System prompts matter far more than most assume. A given model sets the theoretical ceiling of an agent’s performance, but the system prompt determines whether this peak is reached.

The Variety of System Prompts

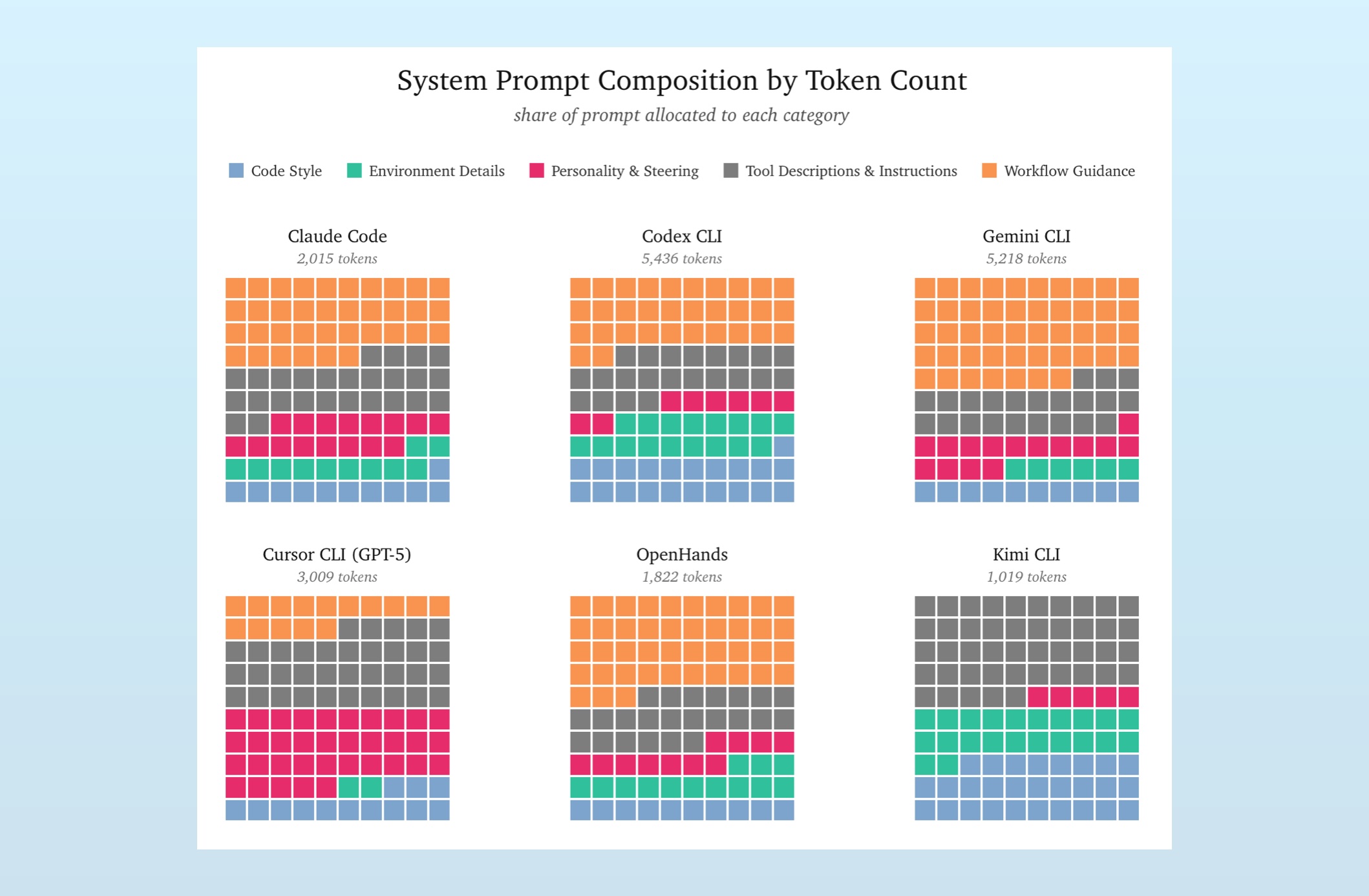

To understand the range of system prompts, we looked at six CLI coding agents: Claude Code, Cursor, Gemini CLI, Codex CLI, OpenHands, and Kimi CLI. Each performs the same basic function: given a task they gather information, understands the code base, writes code, tracks their progress, and runs commands. But despite these similarities, the system prompts are quite different.

We’re analyzing exfiltrated system prompts, which we clean up and host here1. Each of these is fed into context-viewer, a tool Srihari developed that chunks contexts in semantic components for exploration and analysis.

Looking at the above visualizations, there is plenty of variety. Claude, Codex, Gemini, and OpenHands roughly prioritize the same instructions, but vary their distributions. Further, prompts for Claude Code and OpenHands both are less than half the length of prompts in Codex and Gemini.

Cursor’s and Kimi’s prompts are dramatically different. Here we’re looking at Cursor’s prompt that’s paired with GPT-5 (Cursor uses slightly different prompts when hooked to different models), and it spends over a third of its tokens on personality and steering instructions. Kimi CLI, meanwhile, contains zero workflow guidance, barely hints at personality instructions, and is the shortest prompt by far.

Given the similar interfaces of these apps, we’re left wondering: why are their system prompts so different?

There’s two main reasons the system prompts vary: model calibration and user experience.

Each model has its own quirks, rough edges, and baseline behaviors. If the goal is to produce a measured, helpful TUI coding assistant, each system prompt will have to deal with and adjust for unique aspects of the underlying model to achieve this goal. This model calibration reins in problematic behavior.

System prompts also vary because they specify slightly different user experience. Sure, they’re all text-only, terminal interfaces that explore and manipulate code. But some are more talkative, more autonomous, more direct, or require more detailed instructions. System prompts define this UX and, as we’ll see later, we can make a coding agent “feel” like a different agent just by swapping out the system prompt.

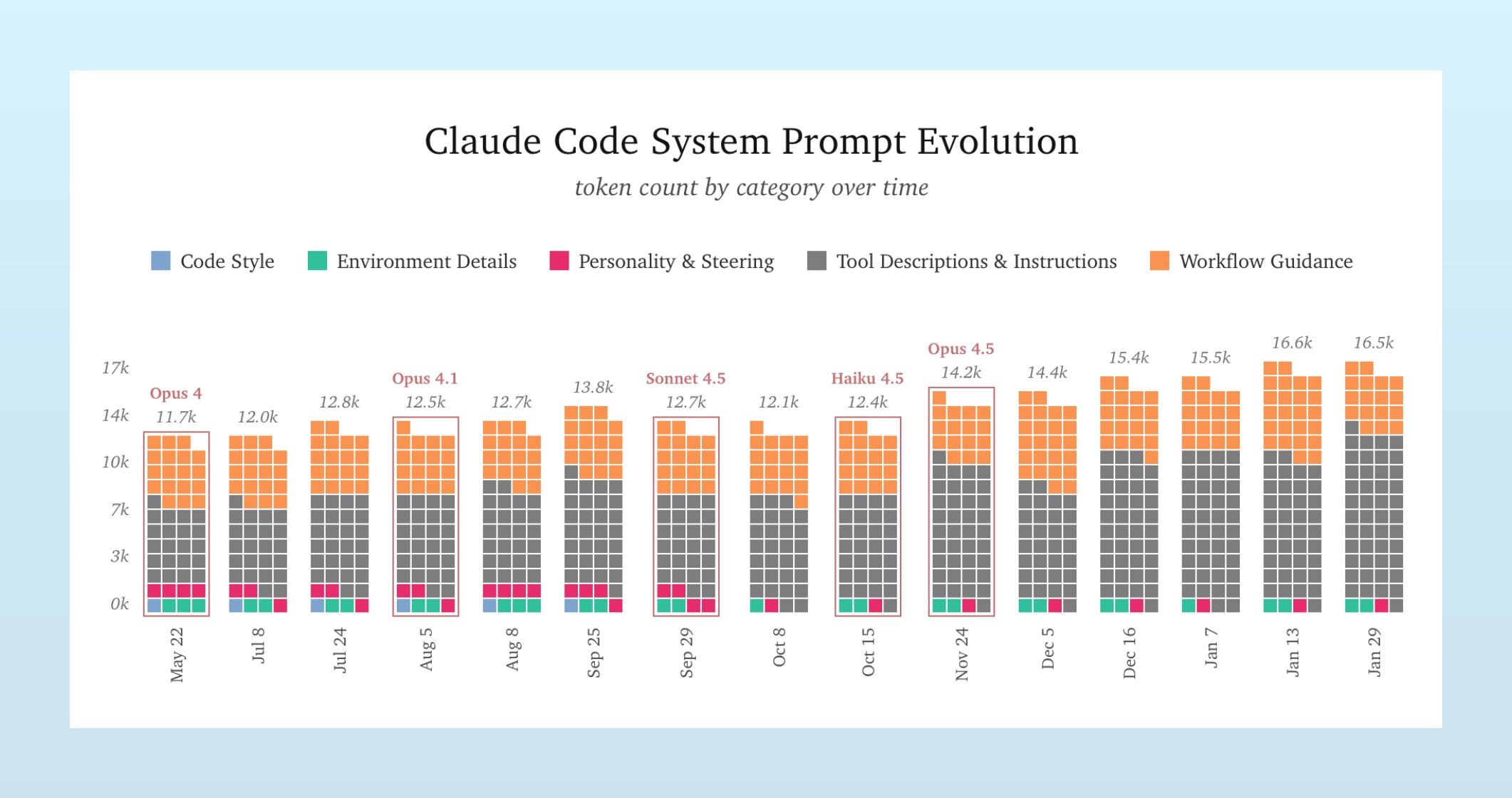

We can get a glimpse of these two functions together by looking at how a given system prompt changes over time, especially as new versions of models arrive. For example:

Note how the system prompt isn’t stable, nor growing in a straight line. It bounces around a bit, as the Claude Code team tweaks the prompt to both adjust new behaviors and smooth over the quirks of new models. Though the trend is a march upward, as the coding agent matures.

If you want to dive further into Claude Code’s prompt history, Mario Zechner has an excellent site where he highlights the exact changes from version to version.

The Common Jobs of a Coding Agent System Prompt

While these prompts vary from tool to tool, there are many commonalities that each prompt features. There is clear evidence that these teams are fighting the weights: they use repeated instructions, all-caps admonishments, and stern warnings to adjust common behaviors. This shared effort suggests common patterns in their training datasets, which each has to mitigate.

For example, there are many notes about how these agents should use comments in their code. Cursor specifies that the model should, “not add comments for trivial or obvious code.” Claude states there should be no added comments, “unless the user asks you to.” Codex takes the same stance. Gemini instructions the model to, “Add code comments sparingly… NEVER talk to the user through comments.”

These consistent, repeated instructions are warranted. They fight against examples of conversation in code comments, present in countless codebases and Github repo. This behavior goes deep: we’ve even seen that Opus 4.5 will reason in code comments if you turn off thinking.

System prompts also repeatedly specify that tool calls should be parallel whenever possible. Claude should, “maximize use of parallel tool calls where possible.” Cursor is sternly told, “CRITICAL INSTRUCTION: involve all relevant tools concurrently… DEFAULT TO PARALLEL.” Kimi adopts all-caps as well, stating, “you are HIGHLY RECOMMENDED to make [tool calls] in parallel.”

This likley reflects the face that most post-training reasoning and agentic examples are serial in nature. This is perhaps easier to debug and a bit of delay when synthesizing these datasets isn’t a hinderence. However, in real world situations, users certainly appreciate the speed, so system prompts need to override this training.

Both of these examples of fighting the weights demonstrate how system prompts are used to smooth over the quirks of each model (which they pick up during training) and improve the user experience in an agentic coding application.

Much of what these prompts specify is shared; common adjustments, common desired behaviors, and common UX. But their differences notably affect application behavior.

Do the Prompts Change the Agent?

Helpfully, OpenCode allows users to specify custom system prompts. With this feature, we can drop in prompts from Kimi, Gemini, Codex and more, removing and swapping instructions to measure their contribution.

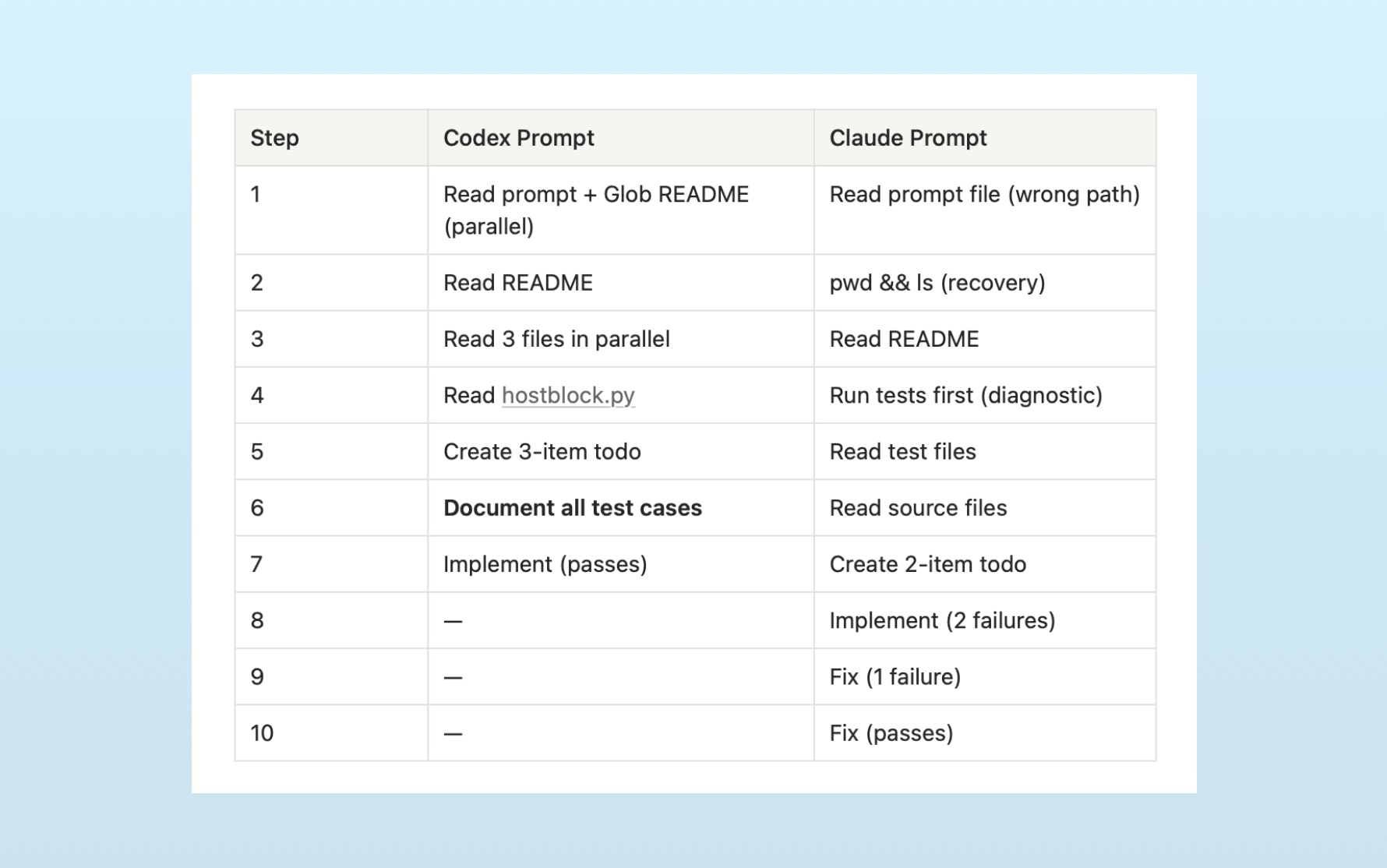

We gave SWE-Bench Pro test questions to two applications: two agents running the Claude Code harness, calling Opus 4.5, but with one one using the original Claude Code system prompt and the other armed with Codex’s instructions.

Time and time again, the agent workflows diverged immediately. For example:

The Codex prompt produced a methodical, documentation-first approach: understand fully, then implement once. The Claude prompt produced an iterative approach: try something, see what breaks, fix it.

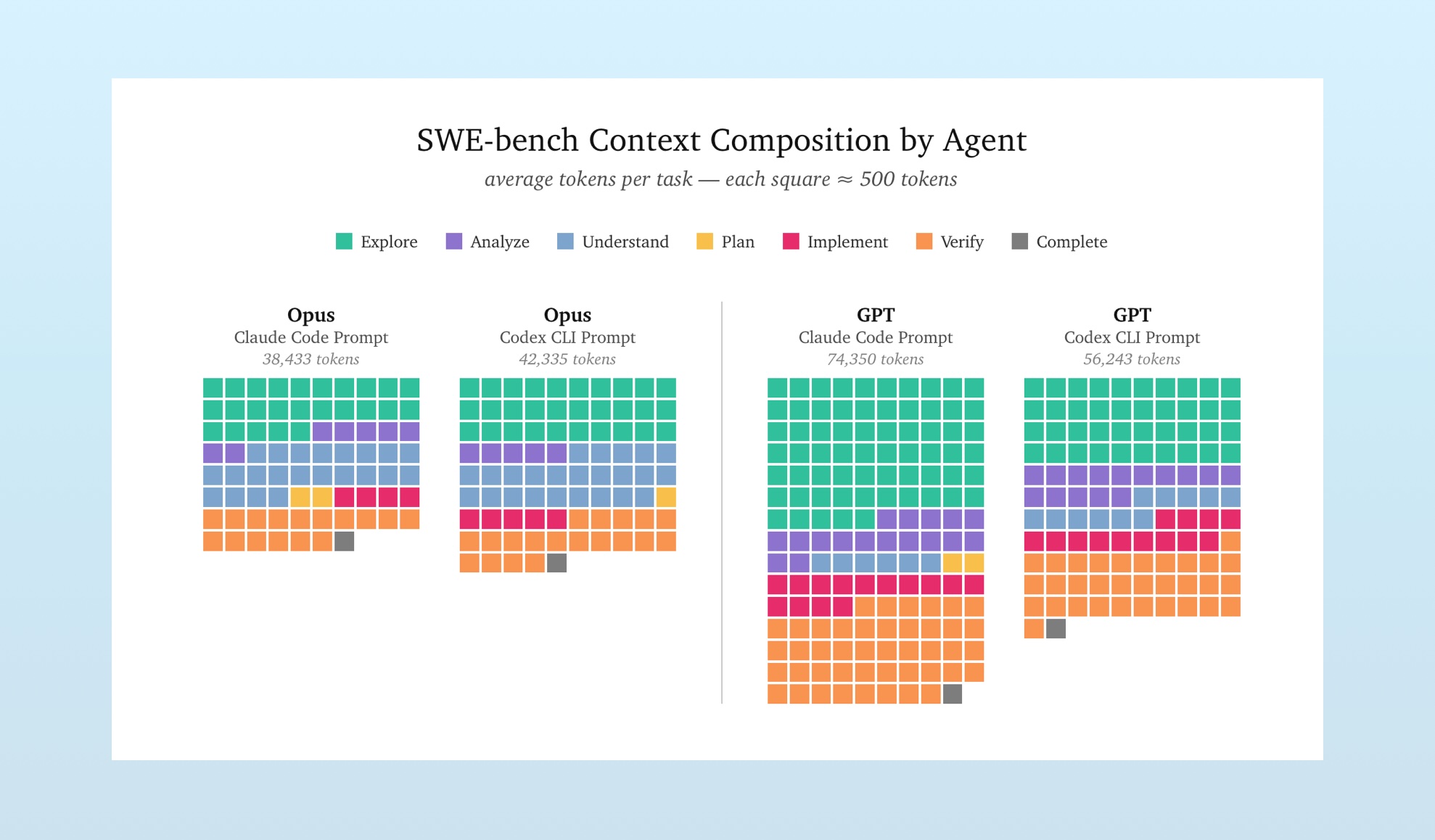

This pattern remains consistent over many SWE Bench problems. If we average the contexts for each model and system prompt pair, we get the following:

All prompt-model combinations correctly answered this subset of SWE Bench Pro questions. But how they suceeded was rather different. The system prompts shaped the workflows.

System Prompts Deserve More Attention

Last week, when Opus 4.6 and Codex 5.3 landed, people began putting them through the paces, trying to decide which would be their daily driver. Many tout the capabilities of one option over another, but just as often are complaints about approach, tone, or other discretionary choices. Further, it seems every week brings discussion of a new coding harness, especially for managing swarms of agents.

There is markedly less discussion about the system prompts that define the behaviors of these agents2. System prompts define the UX and smooth over the rough edges of models. They’re given to the model with every instruction, yet we prefer to talk Opus vs. GPT-5.3 or Gastown vs. Pi.

Context engineering starts with the system prompt.

-

Exfiltrated system prompts represent versions of the system prompt for a given session. It’s not 100% canonical, as many AI harnesses assemble system prompts from multiple snippets, given the task at hand. But given the consistent manner with which we can extrac these prompts, and comparing them with public examples, we feel they are sufficiently representative for this analysis. ↩

-

Though you can use Mario’s system prompt diff tool to explore the changes accompanying Opus 4.6’s release. ↩